Recently lead mobile hardware vendors started to claim that mobile graphics reached the level of modern gaming consoles. Let’s find out whether these claims are true and if so, why don’t we see mobile games which could prove this point.

Vendors base their claims on a single spec parameter: the number of floating point operations that can be performed by a graphical processing unit in a single second. Let’s compare the specs of different devices on both mobile and consoles.

| PS4 | 1843 gflops |

| Xbox One | 1310 gflops |

| Samsung Galaxy S8 | 567 gflops |

| iPhone X | 350 gflops |

| Xbox 360 | 240 gflops |

| PS3 | 192 gflops |

| iPhone 6S | 120 gflops |

From the first glance it seems that the claims are true. Modern mobile devices exceed the capabilities of previous console generations but taking into account the speed of growth, mobile devices will be surpassing the current generation very soon. The question is whether the speed of GPU computation a good way to measure graphics quality? Is there something the industry is not telling us? How do we as programmers ensure we are creating content with the optimum graphics quality?

Behold the everyday horrors of a graphics programmer! I will give you some solutions I’ve learned along the way.

Horror №1: Programming Interface

Widely used APIs like OpenGL and DirectX were developed in the 1990s. Back then graphical hardware was quite different and unfortunately APIs weren’t made to be flexible enough to expose all the capabilities of modern hardware. For example, some current hardware features are being squeezed into the outdated interface, some are exposed by ugly API extensions and others are just inaccessible to developers.

Bye-bye multi-threading

When drawing a picture on a screen, the CPU communicates with the GPU by issuing tasks. These tasks are named draw calls. One rendered image could consist of tens or thousands of draw calls. Each call requires some CPU resources to prepare the textures, models, and other required data. Modern CPUs are multicore, they could handle this load by preparing draw calls in multiple, parallel threads to save time. Unfortunately, outdated APIs have a single global state which makes it impossible to send GPU tasks in parallel. This problem is not unique to mobile devices. If you ever checked the CPU load on your PC while playing your favorite video game you might notice that one CPU core is loaded to almost 100% while all other cores are resting. This is a bottle neck created purely by the software interface.

Flood of shader compilers

Code, which is executed by GPU, is compiled by the driver at the application runtime. This means that all shaders, we graphics programmers write, must be shipped as a source code. Therefore, every GPU vendor must implement their own compilers, including unnecessary syntax validation. There are so many different shader compilers out there that it is almost impossible to write code that will be compiled without errors by all the versions of drivers along with every possible chipset combination.

Poor memory management

Historically CPU memory was separated from GPU memory as they have different performance requirements. This is still true for PC and consoles. When preparing a draw call, the CPU must copy all the required data (textures, meshes etc.) to the graphic’s memory. On the other hand, separate memory chips would be an overkill for mobile devices as it would require more physical space, so both processors usually operate on the same memory on mobile phones. Despite this, interfaces force the CPU to make unnecessary data copies anyway, which creates an additional overhead to processing time.

No programmable blending

Old GPUs had framebuffer color blending implemented on the hardware side, so variety was limited by a set of fixed functions. Currently many graphic chips use programmable blending which theoretically allows us to use any kind of functions, but as you might have guessed, it is inaccessible. Some vendors, like PowerVR, expose programmable blending via special extension but as it is not widely spread and remains mostly unused.

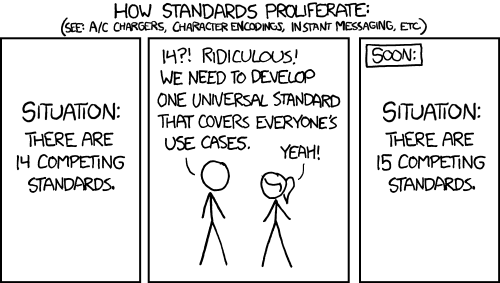

Will APIs be fixed?

Recently a new generation of GPU programming interfaces have arrived. Vulkan is developed by the Khronos Group as a replacement for outdated OpenGL. Unfortunately, war of standards continues as Apple and Microsoft develop their own proprietary APIs called Metal and DirectX12. New generation of interfaces provide lower level access to GPU hardware and allow graphics programmers to solve most of the problems mentioned above. It will probably take some time for new standards to be widely adopted. I think within the next 10 years mobile graphics programmers will be able to exclusively rely on new APIs.

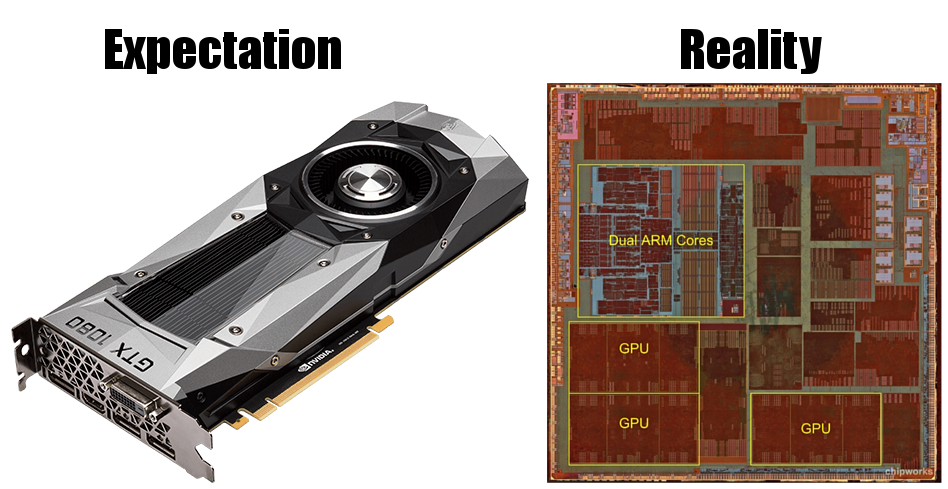

Horror №2: Heat

Compared to PC and consoles mobile GPU and CPU are usually packed into a single chip. Additionally, PCs and consoles use large efficient fans (sometimes liquid coolers :O) while mobiles rely on natural cooling. Consumers want their mobile devices as thin and lightweight as possible.

While physical device parts are getting tinier and more packed in together, they also consume more and more power which leads to increased heat radiation. Natural cooling is reaching its physical limits for mobile devices. In fact, it takes only about 10 minutes, working full power in room temperature environment, for a modern device to overheat. Fortunately, devices are equipped with a protection mechanism to prevent literal burning. When a certain temperature is reached, the device starts throttling the processing unit frequency to cool down. While throttling saves a device from burning, it is devastating for graphical applications and the end user experience.

A small benchmark test performed with the Samsung Galaxy series demonstrates the point. Both device CPU and GPU were loaded to nearly 100% for a duration of 10 minutes. Rendering performance of GPU vertex and pixel programs were measured.

| Model | Vertices (20ms) | Pixels (20ms) | Throttling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galaxy S4 | 500k | 7 screens | No |

| Galaxy S5 | 937k | 20 screens | No |

| Galaxy S6 | 260k | 10 screens | Yes |

| Galaxy S7 | 272k | 15 screens | Yes |

S4 and S5 didn’t overheat at all, keeping the performance on the same level during the whole test. S5 could render twice as much vertices and pixels as its chip has double the power. S6 and S7 could not reach the rendering speed of older devices since their anti-burning mechanisms activated too quickly. This means that Galaxy S5 was the last balanced device and all succeeding ones may not get better performance, as they overheat faster. The same is happening with all other high-end devices produced in 2016 and later.

The question now is, whether vendors are aware of this problem? I think yes, for sure. Why do they keep installing more powerful processors? I think the problem is marketing, consumers tend to trust phone specifications when choosing devices. They don’t realize that specs are just numbers and such processing power can not be achieved in reality.

Probably in a non-capitalistic market, vendors could use their common sense and keep device heat in balance to help app developers use the full potential of the hardware. Are there any Cuban and North Korean mobile phones yet? :)

How to deal with overheating?

The solution should come from the hardware vendors: spec wars should be stopped. Vendors should look more towards cooling and power efficient technologies instead of increasing the processing speed with each device generation. Unfortunately, this problem does not have much resonance with the media, so vendors are not motivated. Though some movement is noticeable in the Apple world. The latest iPhone models (iPhone 7, 8 and X) did not increase GPU performance staying roughly on 350 gflops, while the iPhone X A11 processor with a custom GPU is more power efficient. Media mostly reports this as a step towards longer battery life but the main reason should be the overheating problem.

While there is no complete solution provided by device producers, the responsibility lies on the app developers. The amount of device resource utilisations should be limited to avoid overheating. We approach the problem by measuring the length of the game sessions. For example, average game session for our last project was about 15 minutes long. We decided that keeping 30 frames per second for 15 minutes on all devices should be good enough for most users. After some trial and error, we settled on using about 60% of high-end device resources with the best graphics quality settings. This solved our problem, but limited the image quality for the consumer. If your application requires longer sessions, you have no simple solution but to make the image quality even lower.

Horror №3: Tools

Tools for profiling and analysing mobile GPUs are not standardized. Basically every vendor makes its own tools from scratch. Hardware developers are known to be the worst software makers, so most tools are almost unusable. GPU profilers tend to crash and fail to show the required information or connect to devices. On the other hand, device producers tend to close all possible holes for hardware analysis (security reasons?!). For example, all iOS devices contain PowerVR graphic chips but no official PowerVR tools can be used with those. Fortunately, Apple provides its own proprietary tools, while many Android devices just have no way for low-level hardware analysis.

Will tools become better in the future? Probably not. As the mobile device market expands, the number of hardware vendors has also been growing with no hope for standardisation. Large app development companies make their own tools, but small developers and indie gamedev studios usually don’t have enough resources for that. Though some shortcuts can be used when making analysis tools, check out this article about using Google Chrome Tracing as a profiler frontend.

Horror №4: Diversity

Currently there are hundreds of different mobile GPU models on the market. Each model has several versions of drivers and probably thousands of different CPU+GPU combinations. It is impossible to test all of them even if using automated QA services (P.S. Check out my article on test automation with Unity). Additionally, there are some inadequate combinations on the market with powerful GPUs and CPU too weak to support the power or vice-versa, usually produced by no-name Chinese companies.

In the PC world, developers usually allow users to choose exactly the level of graphics they want to see exposing very detailed graphics settings. This solution does not work well for the mobile game market, as mobile players are not hardcore enough to understand what all these FXAA, SSAO and HBDO mean.

The best solution for mobile app developers is to make 3-4 predefined levels of graphics, using LODs and several versions of post processing effects for optimization. Graphic quality level should be chosen automatically. We map quality presets to device model names on iOS and GPU models on Android. Check out this GDC talk about mobile visuals optimisation.

Conclusion

Well let’s answer the question, whether claims about mobile graphics quality reaching the level of consoles are true? If you read the whole article you might have guessed that answer is NO. Those claims are obscuring the most important part the truth, so I would consider them a lie. GPU vendors are lying as a part of their marketing campaigns. Unfortunately they are forced to do so by the capitalistic competition.

Modern mobile devices are not made for gaming or any other graphically intense applications. First priority for the consumer are everyday tasks like reading emails and browsing Facebook which don’t require much processing power. Device producers will likely keep installing more and more powerful hardware just to keep spec numbers impressive. It seems that mobile graphics is moving toward the dead end, though new cooling and low power consumption technologies (not available at the moment) might change the situation. We might see a truly successful gaming mobile device which will change the market in the future. We shall see.